[author image=”http://echo.snu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/mike.jpg”] Mike Vierow, Editor in chief

Mike Vierow is a senior studying Mass Communication. He enjoys watching movies, reading old dusty books and film photography. [/author]

Let’s take video games seriously for a moment. Despite any other meanings our culture has placed on video games, they are a method of artistic expression. They have the power to emotionally move us and let us see the world through many different perspectives. It may be hard to see this on the surface–there isn’t much eloquent about the latest multiplayer shooter or sports game. But there are video game developers who care about creating a shared experience, one that can be as deep and profound as any novel.

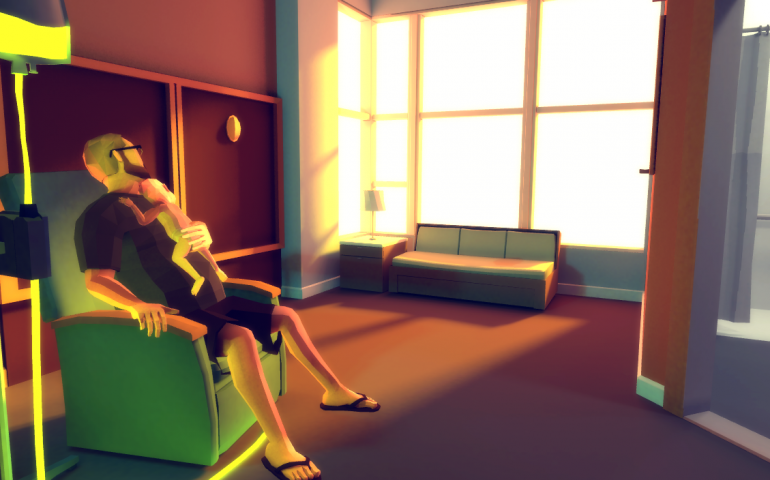

Enter “That Dragon, Cancer.” Created by husband and wife team Ryan and Amy Green, the game tells the story of their son, Joel, who was diagnosed with cancer at the age of one. Through a series of vignettes, the player controls Ryan as the Green family attempts to navigate the internal chaos that is created by a loved one slowly dying. Ryan and Amy are also devout Christians, which has a large influence on how they process the turmoil in their lives.

What astounded me most about “That Dragon, Cancer” was the honesty that the couple put into their story. Creating such a personal work, it would be easy to smooth out the rough edges, to make light of their emotional turmoil and spiritual distress. Instead, the various cutscenes, journal entries, and audio recordings scattered throughout the game convey a sense of confusion and powerlessness. But despite the threat of cancer hanging over their heads, the game features several happier vignettes, such as Joel feeding bread to ducks in a pond or playing with a therapy dog. It was beautiful to see these little moments of joy in an otherwise dreadful time for the family.

Ryan and Amy also used this intense, personal creation to give a space for others who have have had loved ones with cancer. While the game was raising money for its development on Kickstarter, donators had the ability to write short notes to friends or family members, which show up as cards all around the hospital where Joel is being treated. It was almost overwhelming to read the personal and heartfelt writings found throughout the level. In another part of the game, drawings and photos made by cancer patients line the walls of a hospital waiting room. Ryan and Amy could have made this game solely about their family. But instead they chose to let others in so that we may understand what a large effect cancer has on countless people.

Unlike many other forms of Christian media, “That Dragon, Cancer” doesn’t beat players over the head with a sermon. The Green’s faith is a true part of their story, and they don’t fall into the trap of minimizing their struggles in order to be seen as “good Christians”. Throughout the game, Ryan and Amy struggle with God very differently. Amy tends to have a more child-like faith, while Ryan is prone to doubt. Neither is held up as a better way than the other. It was so refreshing to see a work of Christian media that doesn’t see belief in God as a quick fix for all of life’s problems.

Despite the incredible storytelling in this game, it does suffer from a few technical glitches. I found that the point-and-click controls could be a bit tricky to handle, and there were a couple graphical glitches here and there. But these issues in no way diminish the experience of playing through “That Dragon, Cancer.” It is a deeply moving and mature experience, and one that I have thought about almost every day since playing it. I highly recommend anyone who is even somewhat interested in video games play through this unforgettable game.