[author image=”http://echo.snu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/IMG_2377-150×150.jpg”]

Alina Scott, Staff Photographer

Alina is a history major and English minor here at SNU. She is originally from Belize, C.A., and loves reading books, studying history and all things Abraham Lincoln. She has worked as a U.S. history tutor and after grad school plans to become a college history professor. [/author]

In the last year and a half, college campuses across the United States have started to address what can be done to mend the racial divide. Now, the conversation has made it to our beloved SNU. In an attempt to better understand what diversity has looked like at SNU and the Nazarene Church throughout the years, I went to Corbin Taggart, Director of the Fred Floyd Archives. He pointed me to the wide variety of resources (yearbooks, newspapers, manuals, etc.) available in the library and archives. From previous readings, I understood that the 1960s were a time of intense social and political tensions, with issues concerning African American, Chicano, and LGBT civil rights coming to the forefront of the national discussion, so I figured that was a good place to start. From there I expanded it to the ‘50s and ‘70s, so this piece analyzes primary source materials from the Fred Floyd archives from 1950-1975 as well as articles collected from didache.nazarene.org (a Nazarene peer-reviewed online journal). In order to make this piece more reader-friendly, I broke what I found down into three categories: political, social, and religious.

Political

In 1965, Bethany Nazarene College, like many other schools of higher education receiving funding or financial assistance from the Atomic Energy Commission (a program sponsored by the Federal government), was swift to adjust policies that could be viewed as discriminatory in order to be in compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which stated:

“No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Record of that compliance is available on a document, titled “Assurance of Compliance with the Atomic Energy Commission Regulation Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” dated Sept. 1, 1965; this compliance was signed by President Roy Cantrell and assured the school did not engage in discriminatory distribution of federal funds and scholarships. Still, BNC needed to be reminded. (Letter: Deputy Assistant Manager for Administration W.R. McCauley Jr., United States Atomic Energy Commission. Aug. 26, 1965.) From what I could find, there is no evidence to say that SNU, BNC, etc… was legally discriminating against minority students. By all means it was complying with the requirements of the Civil Rights Act. All there is to say is that, for whatever reason, minorities simply did not attend this school.

Social

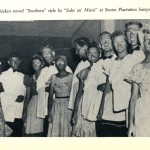

There were highs and lows in BNC’s cultural sensitivity. One low was the hundred year period in which our team name was the “Red Skins.” Another occurred in 1954, when, on the backdrop of an old colonial mansion, the senior class, guests and a faculty advisor attended a banquet. To the sounds of “appropriate negro folk music,” members of the student government in blackface entertained the attendees. This entertainment consisted of servers (also in blackface) singing “Carry Me Back to Ole Virginie,” a “colored waiter” (in blackface) singing “Ole Man River,” and the faculty advisor “imitating Al Jolson, [giving] his interpretation of ‘Mammy.'” In 1964, similar sentiments were reflected during SGA campaign season (1964 yearbook, p. 303) when several students covered themselves in black paint.

Nevertheless, it still appears BNC welcomed diversity in campus life. Although minorities and students of color made up a small fraction of the student body, their presence was definitely felt. Two students of color, Kenneth (Ken) and Lionel Tillett, brothers from British Honduras (what is now Belize) were heavily involved in campus activities. Lionel, an English major, was class chaplain (the equivalent of a campus ministries SGA officer) from his freshman year through to his senior year. He was also recognized in the “Who’s Who” section of both the yearbook and the newspaper for his academic achievements and success. Ken’s participation on campus is highlighted by his time as president of SCOPE, a group of politically minded students that felt the need to form an organization and inform students on issues of international relations. “SCOPE sought to contribute to the advancement of world peace, based on justice and freedom. (1967 Arrow, p. 284)”

Other minority students were active and participating on campus as well. As noted in the compliance reports for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare to ensure BNC’s compliance under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, of the 964 full time undergraduate students at BNC, there were only 23 students of color in 1964. ( There were two listed as “negro,” 6 under “American Indian,” 0 as “Oriental” and 15 in the category of “Spanish Surnamed American.”) By 1972 that number had grown to 25. (“5 American Indian,” “6 Negro,” “0 Oriental,” and “14 Spanish Surnamed American”)

Religious

By the 1960s, the Nazarene Church had been actively seeking out African American pastors to spread the gospel to Nazarene churches springing up in areas occupied by minorities. For that reason, the Nazarene Bible Institute was created. That was in 1948. It wasn’t until 1954 that an African American, R.W. Cunningham, would be appointed president of the school. This stemmed from the increasing number of African American churches springing up in what was, for a ten year period, formally called the Colored District (CD) and then the Gulf Central District. The CD was formed at General Assembly to “give closer supervision and assistance to the (black) churches.” S.T. Ludwig was a part of the committee that oversaw the affairs of the CD.

In conclusion, all I have to say is this. This semester, I’ve heard that the conversation about diversity is “making something out of nothing” or “it wasn’t an issue until you made it an issue.” However, when we reflect on history, it seems the institution was acting within society’s racial expectations as opposed to aiming for better. Personally, in my time here, I would hate to see SNU be guilty of the same things.

References

Fred Floyd Archives

Arrow. Fred Floyd Archives. (yearbook, 1967) p. 84,180, 255, 284.

Arrow.. Fred Floyd Archives.(yearbook, 1964) p. 176, 246, 303.

“Assurance of Compliance with the Atomic Energy Commission Regulation Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” Fred Floyd Archives. (Form, 1964)

“Negro Students Drop-Out Less.” Reveille Echo. (Friday, November 25, 1966. P. 10 )

“Senior Class ‘Visits’ Southern Plantation.” Reveille Echo. Friday, November 20, 1953. p. 60.

Winstead, Brandon. “‘Evangelize the Negro’: Segregation, Power and Evangelization Within the Church of the Nazarene’s Gulf Central District, 1953-1969”.Via http://didache.nazarene.org/

“W.R. McCauley Jr.,“Letter from United States Atomic Energy Commission.” Fred Floyd Archives. (letter, August 26, 1965. )